VIKINGS – THE TOUGHEST WARRIORS EVER by Tyr Neilsen

/PHOTO: HÅKON NEIL

Vikings are the toughest warriors ever according to National Geographic.

The cover of the March 2017 edition of National Geographic has an illustration of a fearsome Viking warrior, sword in hand, glaring out from behind a steel helmet, with the title; Vikings – what you don’t know about the toughest warriors ever.

This 24 page article revals that not only were Viking warriors tough on the battlefield, but that they were tough explorers, seafarers and businessmen.

Using information from the latest scientific discoveries, the article reveals that Vikings traveled further than earlier researchers ever suspected. Using cutting edge seafaring technology they created, Vikings journeyed to over 37 countries, from Afghanistan to Canada.

On their travels they interacted with over 50 cultures, traded using Islamic silver coins, and dressed in Chinese silk and Eurasian caftans.

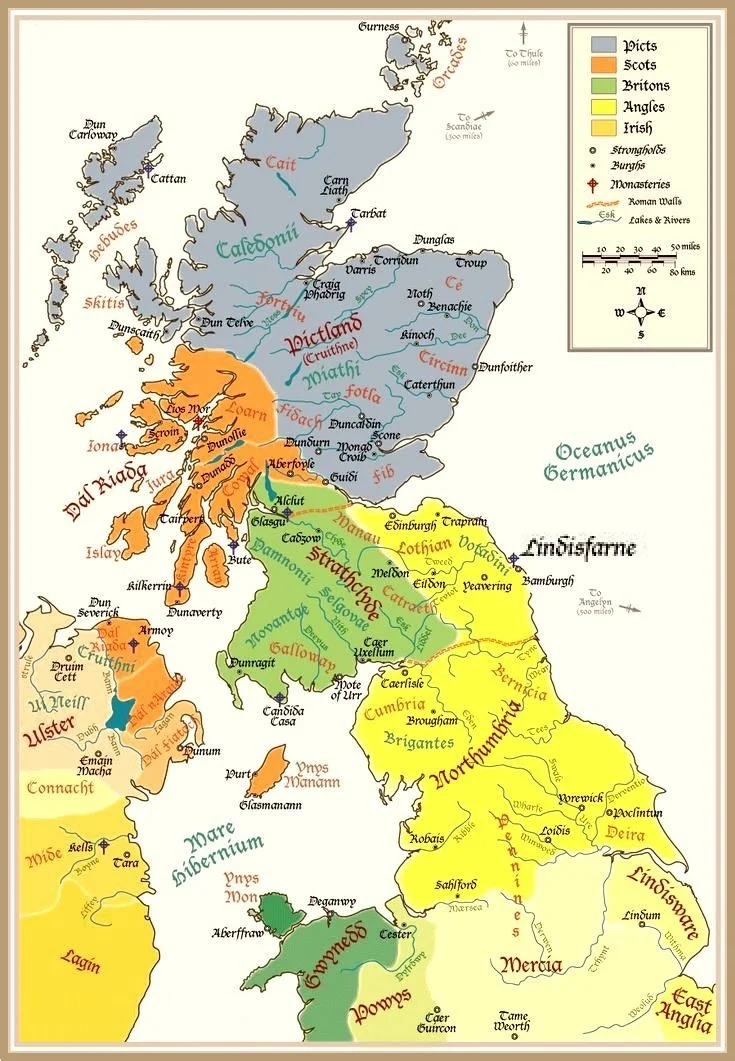

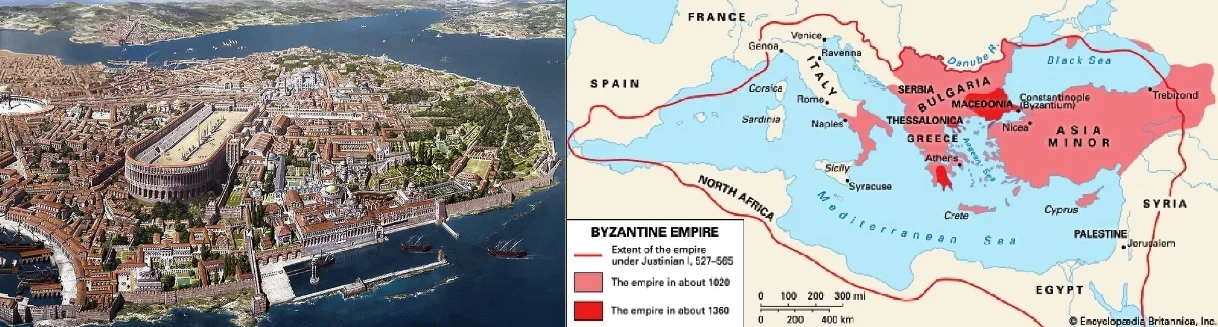

Vikings built thriving cities in York and Kiev, colonized large parts of Britain, France and Iceland, opened up trade routes from Russia to southern Europe, and established outposts in Greenland and North America.

The article states that only Vikings do this, and that no other European seafarers of this period ventured so fearlessly from their homeland.

According to National Geographic, the ambitions and cultural impact of the Vikings can’t be overstated. Sporadic raiding by small groups of Viking warriors evolved into total warfare as Viking armies conquered three Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and impacted world history, but how the people of the north became such a fierce force lies in the 300 year period before the Age of the Vikings.

TOUGH TIMES CREATE TOUGH PEOPLE

Beginning in the year 536, the lands to the north were wracked by turmoil when a series of natural disasters struck. A combination of cataclysms such as comets or meteorites smashing into Earth and at least one volcano eruption, created a vast cloud of dust that darkened the sky and covered the sun for a whole year. For the next 14 years, summer temperature plummeted, and the cold and darkness brought death and ruin to the northern lands.

These extreme weather events were the most severe and prolonged short-term periods of cooling in the Northern Hemisphere in the last 2000 years. The effects were disastrous and caused crop failures and famine.

The more than 35 petty northern kingdoms that had risen in power and territory, and had built chains of hill forts to protect them, now began to fall. In Sweden’s Uppland region, 75 percent of villages were abandoned as villagers succumbed to starvation and fighting for survival.

This dire disaster is likely the inspiration to one of the darkest of world myths; Ragnarok, the end of all things and the last battle of the gods.

When the dark clouds finally dissipated and the sun was able to shine on the land, warm weather returned and the northern people rebounded. Only this time, Norse society assumed a more truculent form.

Chieftains became more aggressive and their heavily armed armies began seizing and defending abandoned territories. This new warrior society celebrated the virtues of fearlessness, aggression, cunning and strength.

In this period of weaponized growth, a new energy effected all peoples of Scandinavia. Skilled carpenters created new technologies and the sleek and deadly longships they built allowed Norse warriors to sail farther and faster than ever before.

This revolutionized Norse society of newly ambitious men, wifeless young warriors, and new type of ship, created the perfect storm.

Northmen who had little chance of marriage or wealth back home, began aggressively exploring new lands, raiding towns and villages, and taking home treasure, slaves and women. The success of these warriors would set Europe afire.

VIKING TOUGH

Only the strong survived the chaos after the natural disasters that hit Scandinavia in the 6th century. The rugged wild nature and six month winters of the northern lands had for generations ensured that the people who lived there were tough, but this new Norse warrior society was even tougher.

A warrior mentality was instilled in Scandinavian boys, and they were trained for combat from a young age.

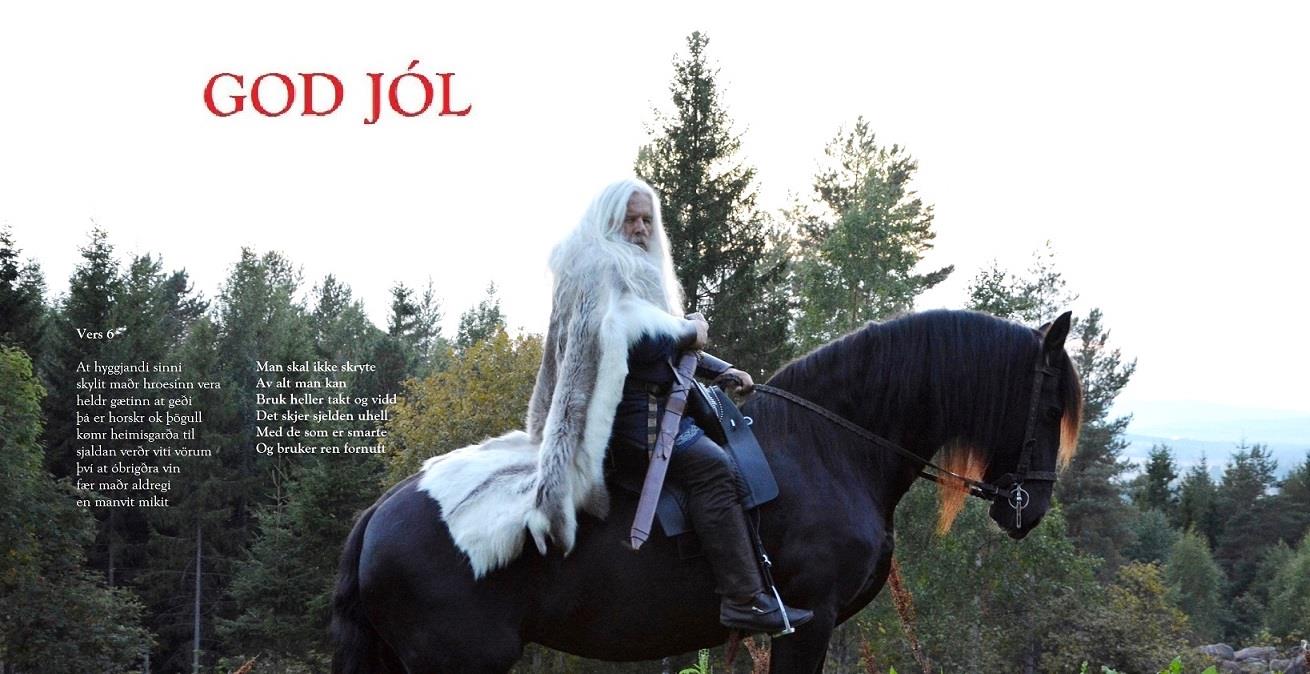

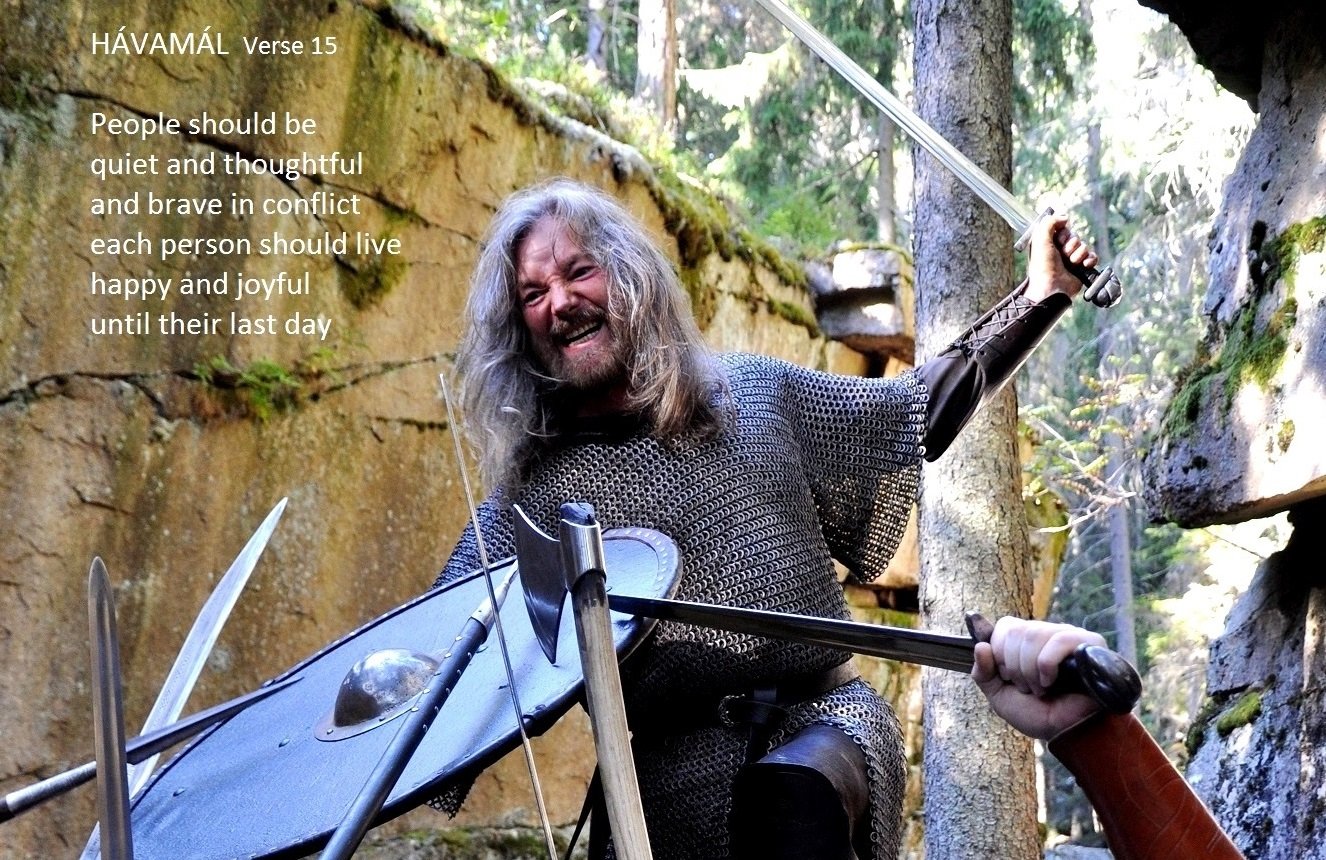

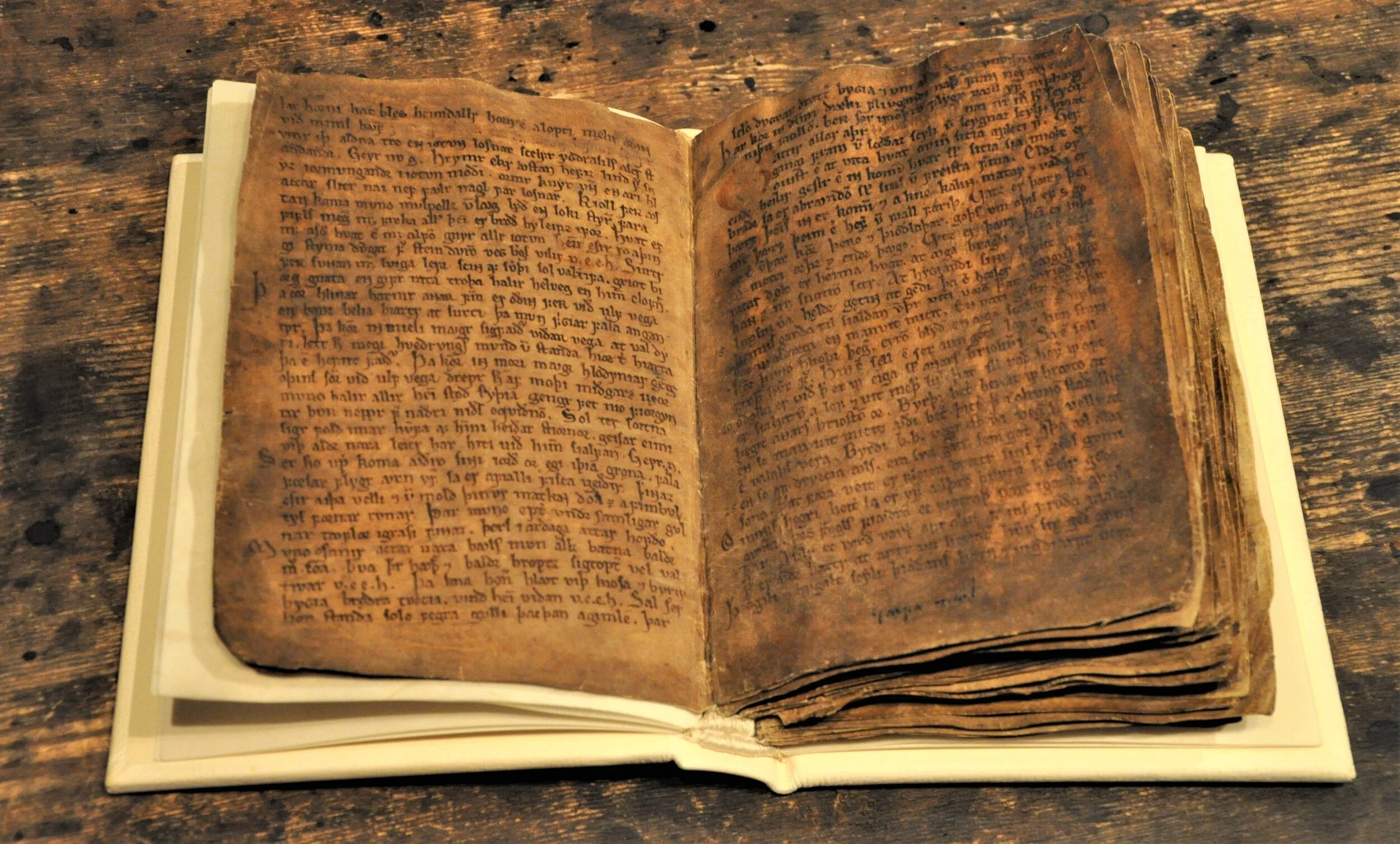

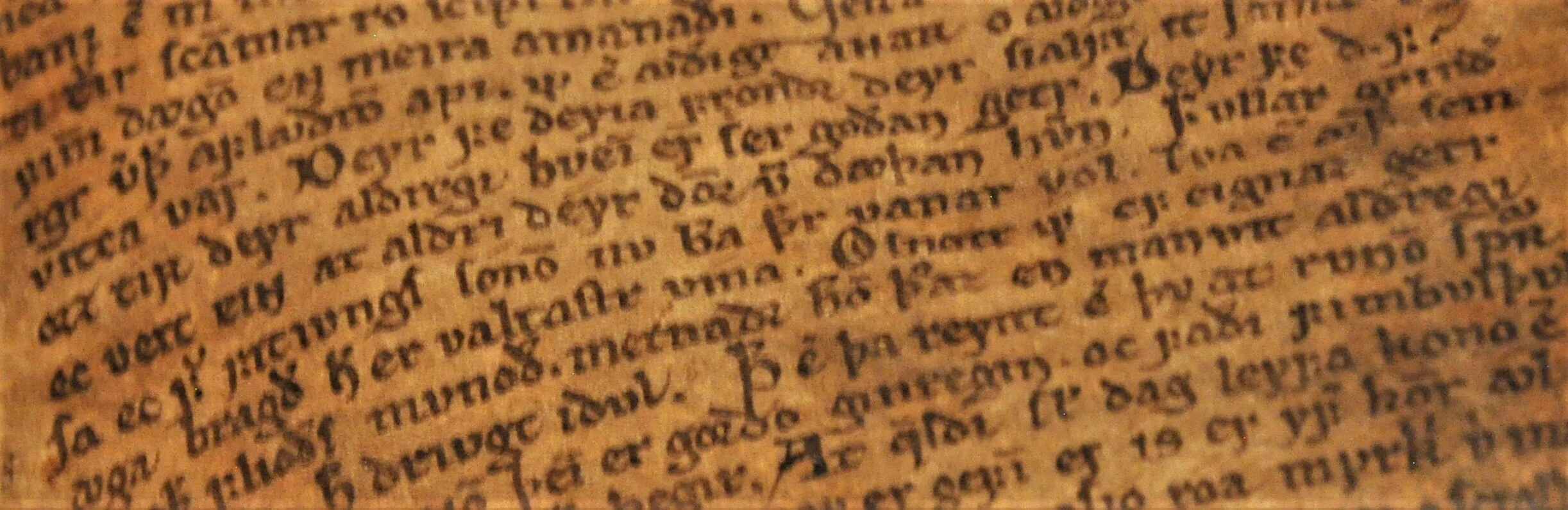

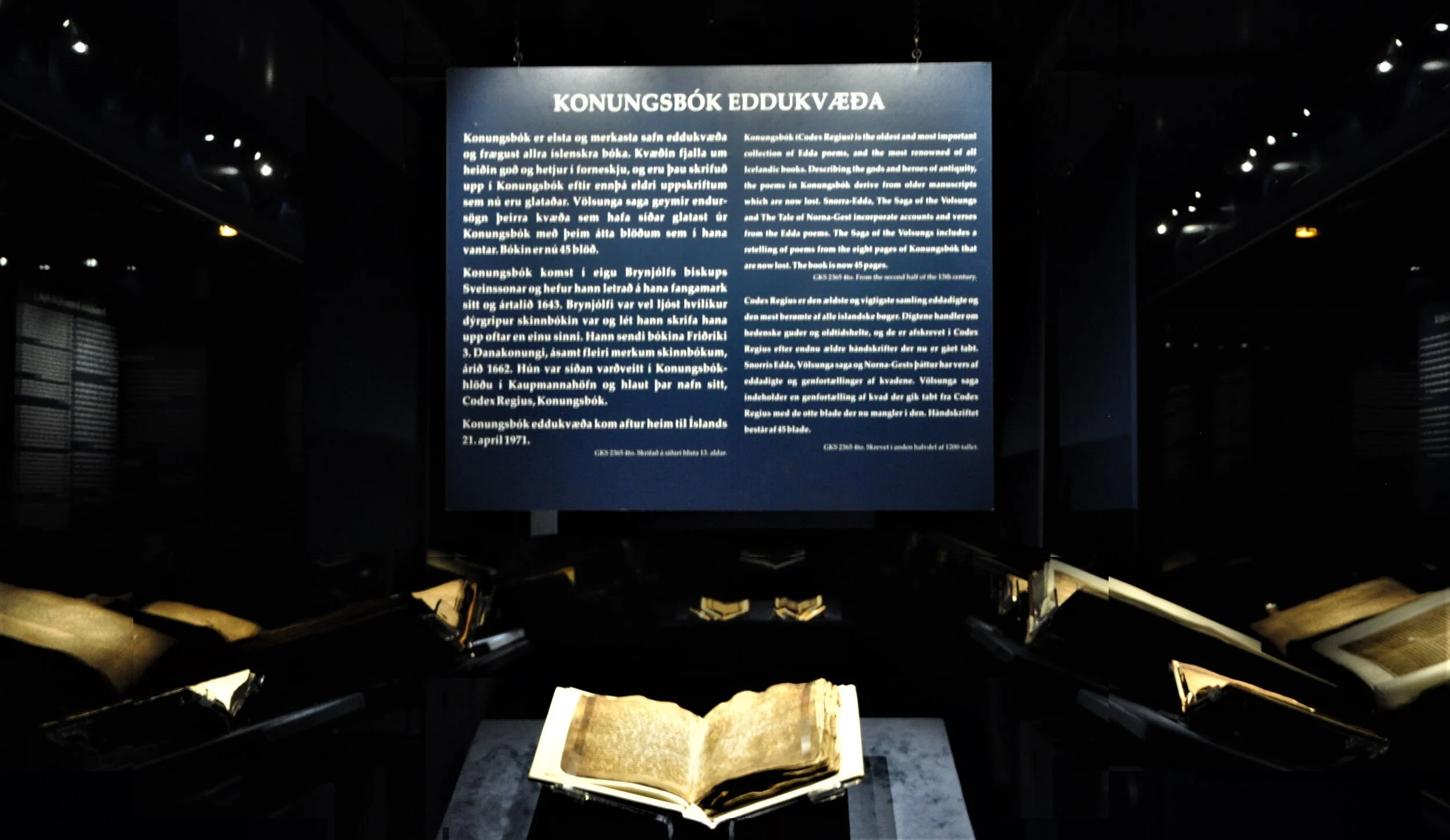

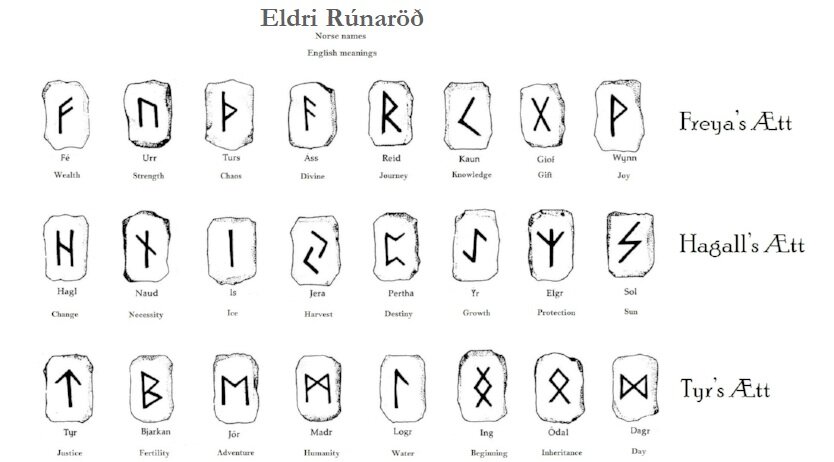

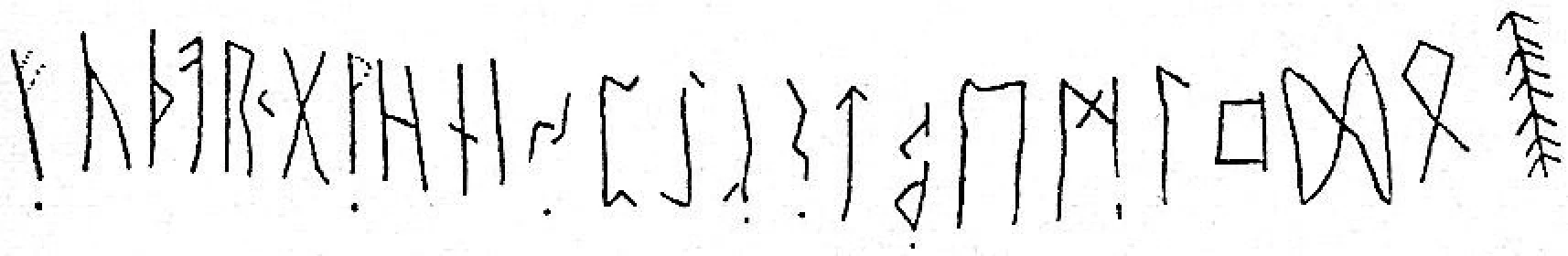

Weapons became extremely important in this warrior society, and according to the Hávamál, a Northman should not be more than a few steps away from his weapons. Archeologists on the Swedish island of Gotland have found significant proof of the importance of weapons in Norse society, where nearly every man was buried with weapons.

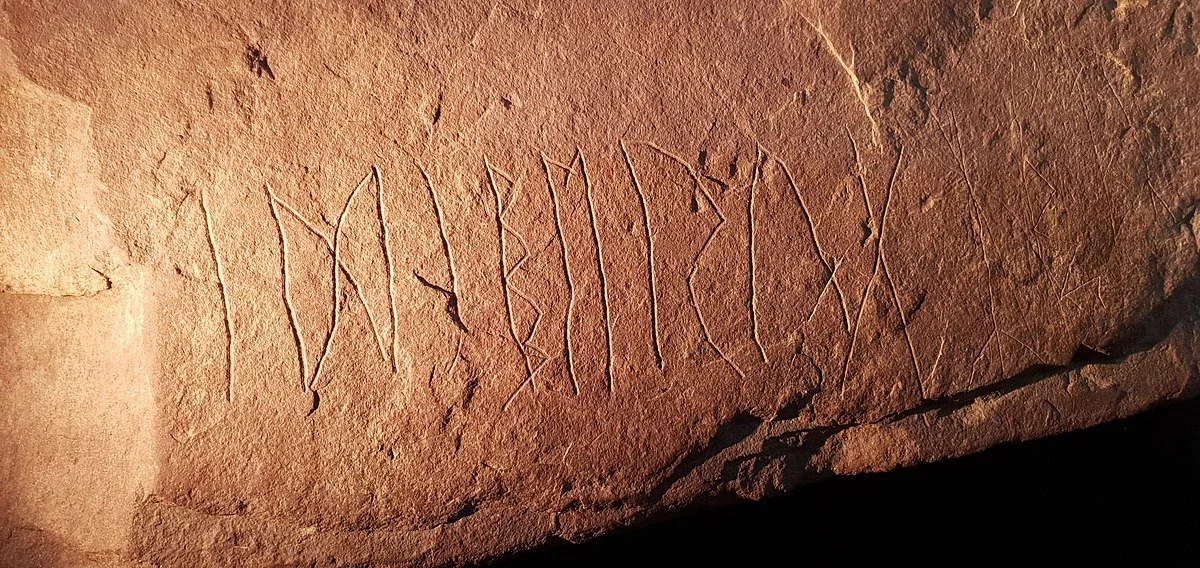

The remains of SCANDINAVIAN men were buried in the ship that THEY SAILED to an Estonian island a HALF century before the Viking AGE BEGAN

In around the year 750, about 50 years before the Viking Age officially started, a band of Norse warriors from Uppsala in Sweden, sailed to the island of Saaremaa, off the coast of Estonia. 40 of these warriors were killed in a battle there and buried in two longships.

In 2008 this burial was discovered by accident, and the discovery caused a stir among specialists, because of all the swords buried with the warriors. Most experts had assumed that Norse raiding parties consisted of a few elite armed warriors, with the rest of the crew made up of poor farm boys with cheap spears and longbows.

What the archeological discovery shows is that the burial contained more swords than men, which could mean that even the earliest expeditions consisted of many Norse warriors of high status.

At some point during this aggressive movement, the term Viking was used for warriors who went out on these voyages of exploration and conquest.

The social hierarchy of the northern lands was slave, freeman, warrior, chief, noble and king, but after a while, the term «Viking» was used to describe all the peoples of Viking Age Scandinavia.

TOUGH TRAILS

The Viking Age officially started when the new breed of weaponized Northman, now called ‘Viking’, raided a monastery in Lindisfarne in the year 793. Successful early raids along the coasts of Europe provided Viking warriors with riches beyond their expectations.

In the beginning these raids were planned for the summer months with just a few longships and less than a hundred warriors.

As Viking warriors grew in strength, experience and motivation, so grew their ambitions. What started as raids on small settlements with just a few longships, grew to attacks on cities like York and Paris with fleets of ships. Viking warriors sailed inland by way of rivers to overthrow kingdoms and seize large swathes of land that they colonized.

In the 9th century, when Vikings raided the France, they stormed more than 120 settlements and extorted 14 percent of the entire Carolingian Empire.

It was not only Viking men that were tough, Viking women were tough too. New discoveries show that leaders of Viking raids were not only battle hardened men, but women such as Inghen Ruaidh «Red Girl» named after the color of her hair, who led a fleet of Viking ships to Ireland in the 10th century.

In the ancient Viking trading center of Birka in Sweden, the skeletal remains of a Viking fighter, buried with an arsenal of weapons, has been discovered to be that of a female. The way she was buried suggests she had the respect of Viking warriors.

"A viking selling a slave girl to a persian merchant" by Tom Lovell